Sir Francis Drake and the Human Face of Caribbean Exploration

When we speak about Sir Francis Drake in the Caribbean, it is tempting to picture only the legend. The fearless privateer. The enemy of empires. The man whose name echoed with fear in Spanish ports. But when we slow the story down and place it among the islands, among the heat, the uncertainty, and the long days at sea, a more human figure emerges. Grenada, and the waters around it, belong to that quieter, truer version of the story.

In the late sixteenth century, sailing the Caribbean was not heroic by design. It was exhausting, dangerous, and deeply uncertain. Ships were not fast by modern standards. They were wooden, heavy, and alive in their own way, groaning under strain, leaking constantly, demanding care every hour of the day. Crews lived close together, often sick, often afraid, always dependent on one another. The sea did not forgive mistakes, and neither did distance.

Sir Francis Drake

by Unknown artist, oil on panel, circa 1581, 71 3/8 in. x 44 1/2 in. (1813 mm x 1130 mm)

Sir Francis Drake knew this life intimately. He first came to prominence sailing with his cousin John Hawkins, one of the most influential ship owners and commanders of the time. Hawkins’ fleet included ships such as the Jesus of Lübeck, a massive and powerful vessel owned by Queen Elizabeth I herself, as well as smaller, quicker ships like the Minion and the Judith, which Drake would later command. These were not warships in the modern sense. They were working vessels, adapted for trade, transport, and conflict when necessary.

Their early voyages into the Caribbean were brutal lessons. In 1568, the English fleet was trapped and attacked by Spanish forces at San Juan de Ulúa in present-day Mexico. Many ships were lost. Many men did not return. Drake survived, but the experience marked him deeply. It taught him that survival in the Caribbean depended not on strength alone, but on timing, wind, local knowledge, and the ability to disappear into the sea when needed.

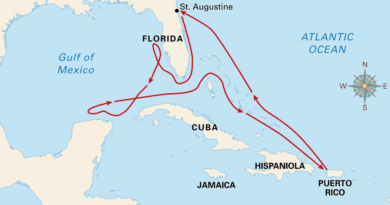

In the years that followed, Drake returned to the Caribbean with a different approach. Commanding ships like the Pelican, later renamed the Golden Hind, and smaller, faster vessels designed for agility rather than firepower, he began to exploit the same routes Spanish sailors relied upon. Grenada sat near the southern edge of these networks, a place known to mariners for fresh water, shelter, and as a waypoint within the trade wind system. It was not heavily fortified, but it was well known among sailors who truly understood the sea.

Drake was not alone in these waters. Spanish captains such as Pedro Menéndez de Avilés and Álvaro de Bazán had already shaped Caribbean navigation through disciplined fleets of galleons, massive ships designed to carry treasure and defend it. French privateers, operating from smaller ports and often sponsored by noble families, used lighter ships to raid and retreat quickly. Indigenous Caribbean sailors, whose names rarely appear in European records, moved through these islands in canoes and small craft, holding generations of knowledge about currents, reefs, and seasonal winds.

What made Drake exceptional was not that he sailed where others did not, but that he listened more carefully. He learned from captured pilots. He observed how wind wrapped around islands like Grenada. He noticed where large galleons struggled to maneuver and where smaller ships could slip away. His famous raid on Nombre de Dios in 1573, and later his interception of Spanish silver convoys, were not acts of brute force. They were acts of patience, planning, and deep respect for the sea’s rhythms.

The ships themselves were characters in these stories. The Golden Hind was no giant. She was strong, well-built, and reliable, owned by a syndicate of English investors who trusted Drake with their fortunes and their hopes. Her success was not inevitable. It was earned through constant vigilance, repairs at sea, and the quiet courage of sailors whose names history rarely remembers.

Around Grenada, these same types of ships passed regularly. Spanish supply vessels, English privateers, French traders, and local craft all crossed paths, sometimes peacefully, sometimes violently. Each crew carried fear, ambition, hunger, and homesickness. Each sailor looked at the same horizon and wondered what waited beyond it.

To humanize this history is to understand that Drake’s achievements were not moments of triumph alone. They were long stretches of uncertainty punctuated by brief flashes of success. They were built on trust between captain and crew, on shared hardship, and on an intimate relationship with wind and water. Grenada did not witness grand declarations or final victories. It witnessed continuity. Ships passing. Sails rising and falling. Decisions made quietly on deck at dawn.

Today, when modern sailboats race these routes, they do so with lighter hulls, advanced sails, and instruments Drake could never imagine. Yet the feeling is not so different. The wind still arrives from the same quarter. The currents still slip by unnoticed unless respected. The islands still demand attention rather than conquest.

Takeyway from GrabMyBoat

Sir Francis Drake’s true achievement in Grenada and the wider Caribbean was not domination, but understanding. He learned how to move through this world without forcing it. He trusted the sea enough to let it carry him, and skilled enough to know when to yield. That legacy belongs not only to him, but to every sailor, named and unnamed, who passed these islands under sail and left a trace only in memory and wind.